As the threat of strategic bombing loomed over Japan from the middle of the Pacific War, the development of effective extreme-caliber aircraft guns was expedited by the Japanese Army. New weapons with calibers ranging from 47 millimeters to as much as 150 millimeters were developed and were planned to be deployed on various interceptor platforms.

These weapons – capable of destroying a strategic bomber in just one hit – were naturally only suitable for installation in the heaviest fighters of the time, due to their massive size, weight, and recoil force. For cannons 75 millimeters or more, even most two-engine fighters would be insufficiently sturdy or suffer severe performance detriment.

For this reason, the Army’s Type 4 Heavy Bomber ‘Hiryū’ (Ki-67) was selected as the basis for such an interceptor. The Type 4 was closer to the international standard of a ‘medium bomber’ but possessed an excellent top speed (537 km/h) and exceptional maneuverability for its class. The weapon of choice was the Type 88 7 cm Field-AA Cannon, a mobile 75mm anti-aircraft gun used by the Japanese Army since 1928.

The aircraft-adaption of this cannon has often been identified as the ‘Ho-501‘ in both Japanese and English publications. However, through the examination of extant historical materials, it seems evident that this was an error. Ki-109, the features of its gun, and the theory about the Ho-501 will be explained in this article.

Planning of Special Air Defense Fighter, Ki-109

The genesis of the Type 4 Heavy Bomber’s interceptor-adaption was with a new prototype order issued by the Army on November 20th, 1943. By this time, Japanese intelligence had already perceived the impending threat of the B-29 Superfortress.

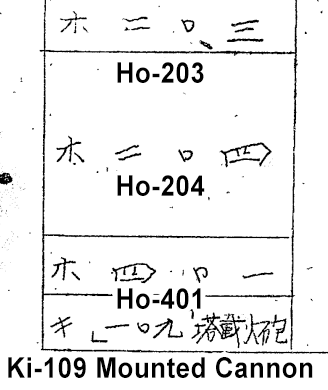

The request was to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for the development of a Type 4 Heavy Bomber modification designated ‘Ki-109’ in two models: ‘Ki-109 Kō’: a Patrol & Air Defense Fighter equipped with double dorsal, upward-firing ‘Ho-204’ 37mm machine cannons, and ‘Ki-109 Otsu’: a Foe-Searching & Illuminating Plane equipped with a 40cm search-light. In night operations, these two planes were planned to cooperate in “hunter-killer teams” to bring down strategic bombers.

Two of these in an inclined mount were the guns of the original Ki-109 plan.

However, it was not long before this plan was adjusted by the opinion of Army Major Hideo Sakamoto. Major Sakamoto preferred the concept of mounting a Type 88 7cm Field-AA Cannon, which he theorized could fire from outside the envelope of the B-29’s defensive guns and score a certain kill in one hit. This replacement plan was ordered in January 1944, abolishing the variants with night-fighting equipment and making Ki-109 a single model. Within the adjusted plan, the first prototype of Ki-109 was scheduled to be completed in May 1944, followed by the second in June.

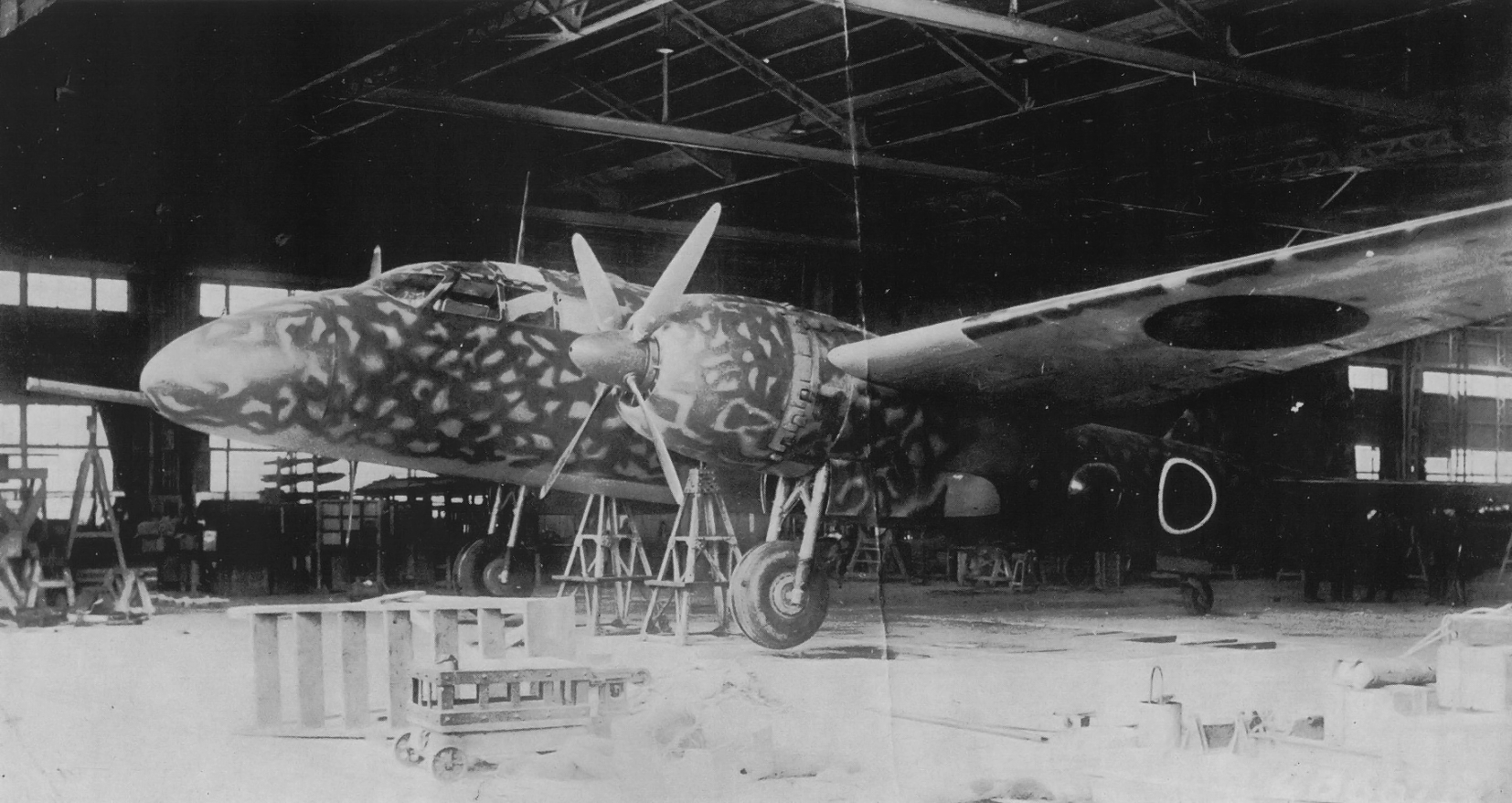

The design team was led by Mitsubishi Engineer Ozawa, and the process progressed rapidly during the early part of 1944 under the expectation of the B-29’s arrival. The examination of the full-scale wooden mockup was held on February 11th, 1944. To improve visibility while diving, it was requested that the shape of the nose be changed to a shape steeply curved downward in comparison to the original Type 4, and this was reflected in the design.

The defensive armament remained intact for the prototypes.

The design was completed in March 1944, and construction of the first two prototypes started. Rather than building from scratch, two Ki-67s owned by the Army Examination Department were remodeled with a new nose, and the defensive armament remained intact. It seems that in the early stage of development, it was hoped that the Ki-109 could retain its defensive weaponry to have a fighting chance against escort fighters.

The first prototype was completed in August, three months later than planned. Its maiden flight took place on August 30th, where it was demonstrated that the maneuverability of the plane had not significantly deteriorated from the original Type 4. The prototype was subsequently flown to the Fussa Airfield in September for ground firing tests, and the second prototype was completed at the end of October.

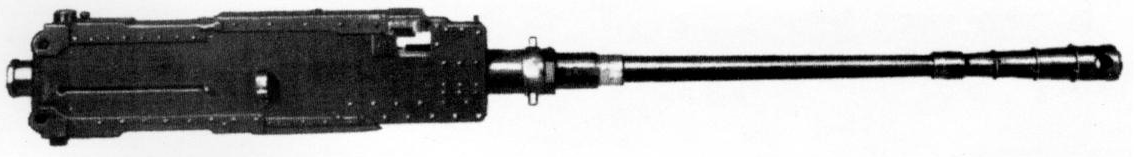

‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon’

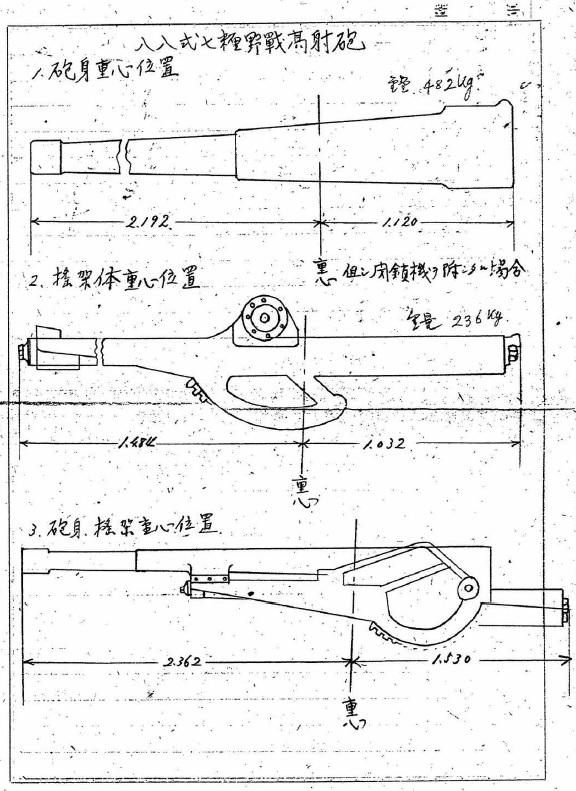

The design of the aerial adaption of the Type 88 7 cm Field-AA Cannon was carried out by the 1st Army Technical Research Institute in cooperation with Mitsubishi, and the Osaka Army Arsenal was responsible for manufacturing. On March 6th, 1944, it was decided that the 1st Institute would complete the design drawings by March 20th. The Type 88 cannons #3582 and #3583 from Osaka Arsenal were chosen as the prototypes, and were to finish being modified to the ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon‘ a month after the design was submitted.

Under the guidance of Major Makiura of the 1st Research Institute, testing was done on standard Type 88 cannons to confirm the recoil characteristics in various conditions. This was to ensure the safe mounting of the gun in an aerial configuration and was carried out from March 22nd to the 28th; the completion report was submitted on the 31st.

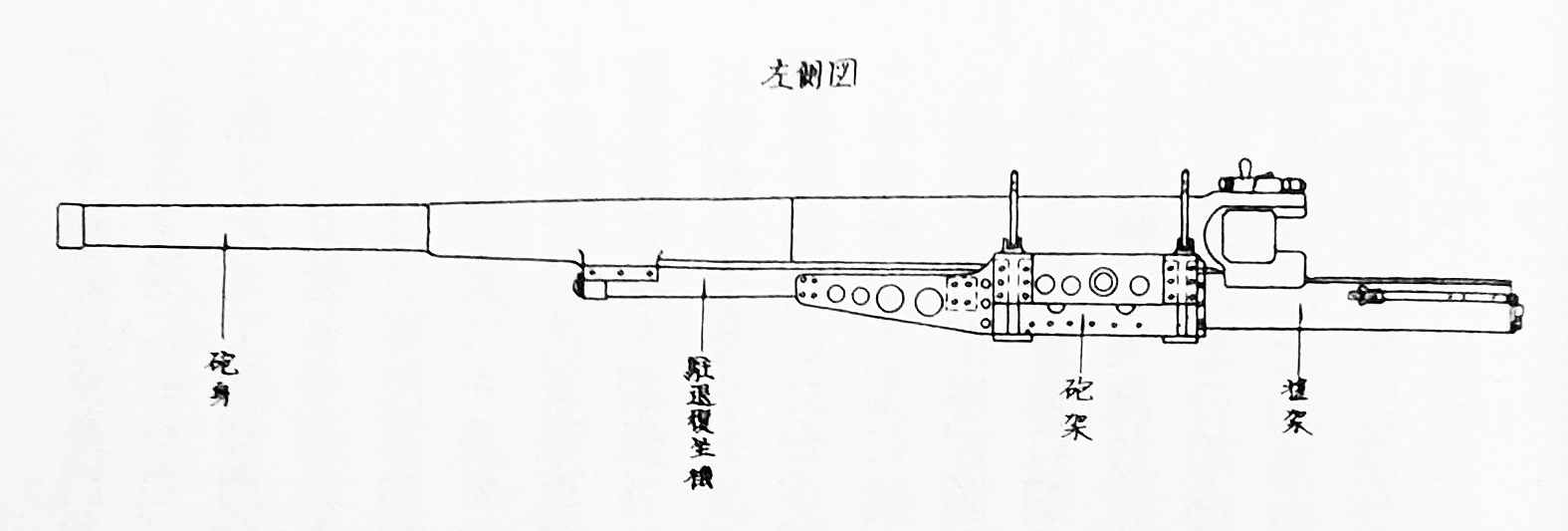

The design modifications to convert the Type 88 to the ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon’, in simple summary, were as follows. The land-based mount and pedestal were replaced with an aerial gun cradle. The firing mechanism was changed to be electrically actuated. The length of the gun’s recoil was reduced from 1.40 meters to 1.32 meters. The operation of the weapon consisted of automatic shell ejection and manual shell loading, with the ammunition stored in a 15-round magazine.

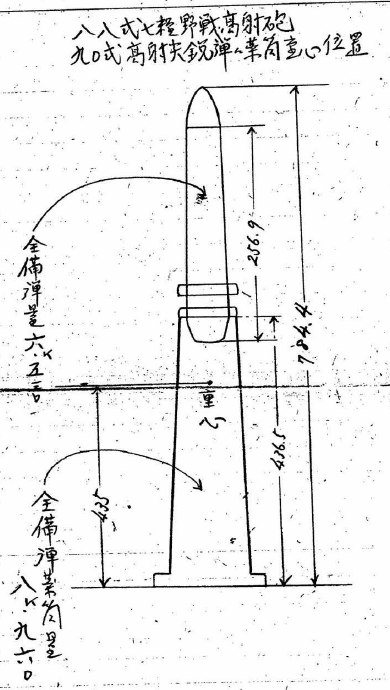

The final specifications of the modified gun were as follows: overall length of 3,892 mm, a barrel length of 3,312 mm, 740 kg overall weight (490 kg barrel weight + 250 kg mount weight), 720 m/s muzzle velocity, and actual caliber of 75 mm. Aiming and firing were done by the pilot, and rather than a co-pilot, there was a dedicated loader’s position. The weapon could, of course, fire any of the shells common to the Type 88. This ammunition pool included the Type 90 & Type 94 HE Shells, Type 90 & Type 3 AA Sharp Shells, and Type 1 & Type 4 AP Shells.

The prototype cannons completed their modification in April 1944 and were tested at the Otsugawa Range from April 24th to the 28th. 86 shells were fired collectively from both prototypes. The completion report for the tests was submitted on May 2nd, and it was considered that the general functions were in order, including the recoil systems, but the electric firing mechanism needed to be revised. There was no damage to the mount when inspected.

The adjusted re-test of the Ki-109 Mounted Cannon was carried out from May 26th to 29th at the Irago Range, with the completion report being submitted on June 1st. The main purpose of this test was to confirm the functionality of the electric firing mechanism and the length of recoil at various angles of fire. Both proved adequate, and the test was completed successfully.

At this point, there is a disparity: primary documentation states that the Ki-109 ground test was scheduled at Fussa and the aerial firing test at Mito. Some secondary sources and recollections state that the ground test was done at Mito and the aerial test at Fussa. I am going with the schedule presented in the documents of the time.

With the arrival of the first prototype Ki-109 to Fussa in early September, the ground firing test of the airframe-installed cannon was carried out. The schedule was to perform the test from September 8th to the 10th, but the actual date is not known. 24 rounds were to be fired with various amounts of propellant to primarily examine the recoil resistance of the airframe. As a result of the testing, it is known that there was damage to the windshield, entry door, and landing light. However, there were no major structural failures, so the result was considered successful, and the necessary reinforcements were made.

The prototype was then flown to Mito Airfield, where aerial firing tests were run at the Mito Range. 39 rounds were to be fired with various amounts of propellant. The target aircraft was a Ki-43II, and targets included 10-meter fabric boards and streamers. When firing on ground targets, the Ki-109 was appraised as having “unparalleled accuracy”, requiring almost no compensation of aim to accurately destroy the target. However, aiming at aerial targets was not as simple. Determining the necessary adjustment of aim was tested by shooting with a 16mm-film gun-cam at a target plane flying over a lake. As the Major flying most of the flights said:

The issue was aiming. It didn’t go well until the end.

Major Sakamoto, 未知の剣 (translated)

| ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon’ Specifications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caliber | 75 mm | Length | Overall | 3,892 mm |

| Cartridge | 75 x 497 mm R | Barrel | 3,312 mm | |

| Muzzle Velocity | 720 m/s | Weight | Overall | 740 kg |

| Rate of Fire | 20 rpm | Barrel | 490 kg | |

| Max Effective Range | 1,500 ~ 2,000 m | Mount | 250 kg | |

| Capacity | 15 rounds | |||

Despite the opinions of the pilot, the firing trials were still generally appraised to be very successful due to high accuracy against static targets. Following these trials, the mass production of 44 aircraft was urgently ordered from Mitsubishi on October 13th, 1944. It was expected that this plane would still be effective against formations of massive B-29s.

Misidentification as “Ho-501”

Since the end of the war, various researchers have identified the aircraft adaption of the Type 88 with the designation ‘Ho-501‘. This seems to be an error.

The Japanese Army developed a large range of aircraft cannon projects during World War II, many of which remain with almost no readily available data. In this situation, it’s easy to see how the error has occured. Army aircraft guns with a calibre of over 11mm used the project-name prefix ‘Ho’ (ex: Ho-5, the Army’s mainline 20mm). Fragmentary data about a 7.5 cm cannon named ‘Ho-501’ seemed to be the solution for the missing ‘Ho’ designation of the Ki-109’s cannon.

As it turns out, the ‘Ho’ prefix only applied to machine cannons. For example, the manually-loaded Type 94 37 mm Tank Gun used on the Ki-45 Kai Otsu did not have a ‘Ho-‘ designation. In the same way, the aero Type 88 was only ever referred to in documentation as the ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon‘.

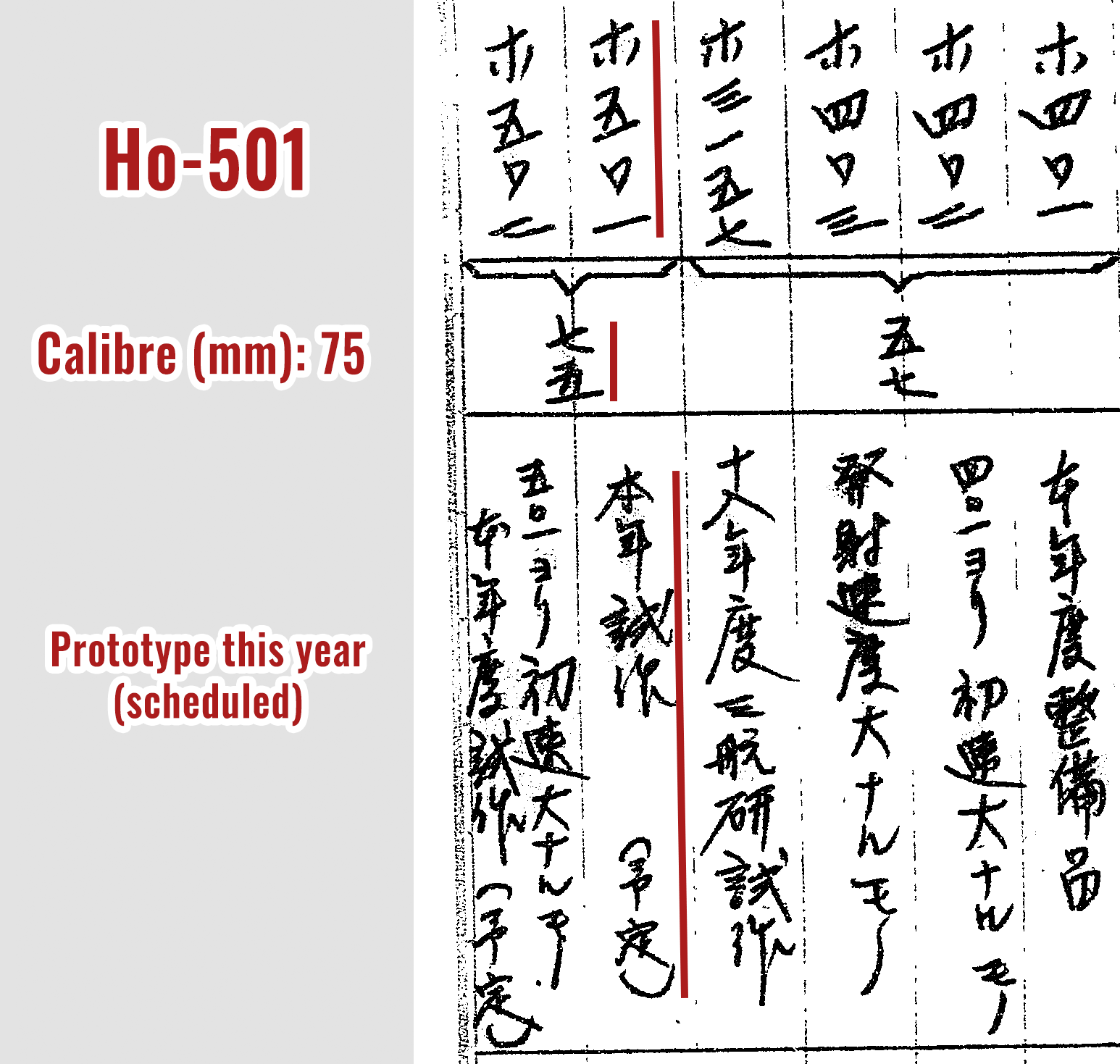

There are a few documents that definitively separate ‘Ho-501’ from the ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon’. First of all, a table of machine cannons made in July 1944 by the Army. At this point, Ki-109’s cannon was already being tested, but the completion of the Ho-501 is still “scheduled”.

In the American document ‘Ordnance Technical Intelligence Report #19‘ made after the war with Japanese data, the Ho-501 is identified as a 7.5 cm recoil-operated machine cannon with a velocity of about 500 m/s and a rate of fire of about 80 rounds per minute. From the specs it can be deduced that this is essentially an automatic adaption of an ‘infantry’ type gun, like the 37mm Ho-203 and 57mm Ho-401, giving a mediocre velocity and fire rate probably intended for use on large bombers or ground targets. The gun was not completed before the end of the war according to the document.

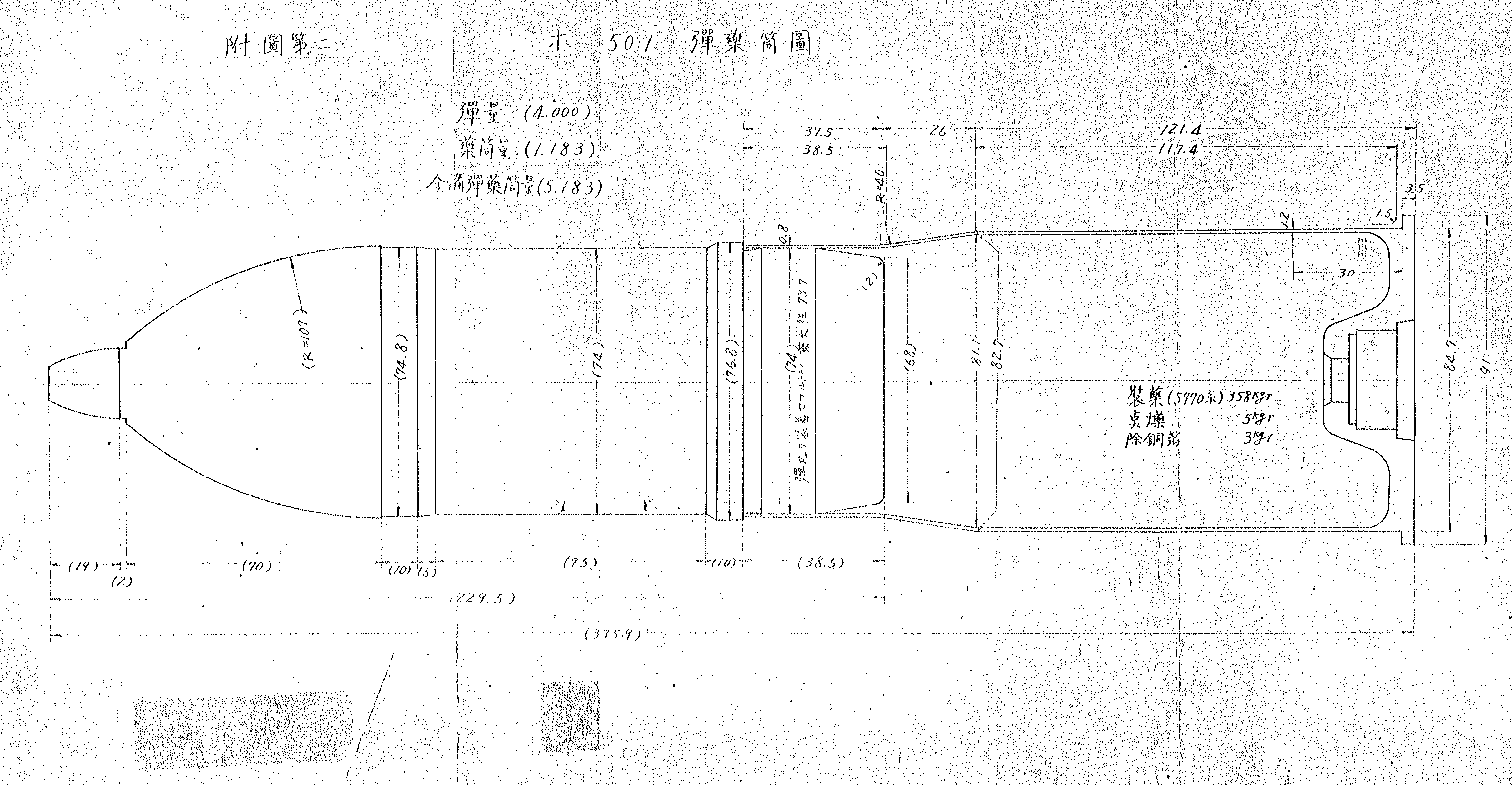

Finally we are fortunate enough to have a detailed piece of data submitted by the Army to the US occupational authorities regarding this machine cannon: the diagram of the Ho-501’s shell. The diagram shows a high-explosive shell with the same cartridge as the Type 41 Mountain Gun, 75x185R. Therefore, we can say that the Ho-501 was sort of an ‘automatic Type 41’, albeit with a higher velocity.

It is proven from these materials that the Ho-501 was an entirely different weapon than the ‘Ki-109 Mounted Cannon’. Furthermore, the Army had projects for several more 7.5cm machine cannons, and even 12cm and 15cm machine cannons, which may be part of a future article.

Ki-109 in Combat

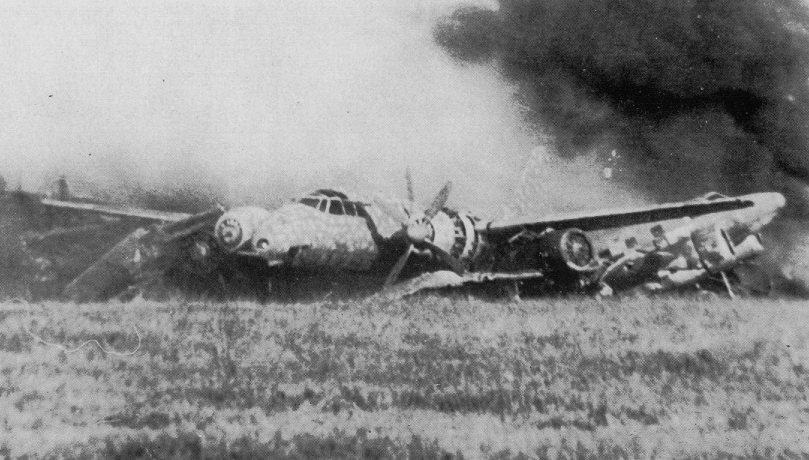

Starting from November 1944, either of the Ki-109 prototypes were piloted in real interception missions against B-29 formations over the region around Fussa. This was the ‘actual combat testing’ of the Ki-109.

On the first mission, Major Sakamoto was at the controls. He climbed to an altitude of 10,000 meters over Fussa and waited to intercept a formation of 30-40 B-29s at 9,000 meters. Gently descending towards a group of five planes, he fired around 10 successive shots with a 1,500-meter timed fuse. No effective hits were scored, and the B-29s increased throttle to escape. The non-turbocharged engines of the Ki-109 had obviously inferior retention of power than those of the B-29, and they pulled away.

Captain Otsuka was the pilot of the second attempt. Rather than approaching from behind as in the first try, he attacked from the front. All the same, no hits were scored, and the Ki-109 sustained .50 caliber hits to the left wing in return. Once again, it returned to the airfield without success.

For the third and final attempt, Sakamoto was back in the pilot’s seat. But the conditions were hazy with poor visibility, and although he performed an attack, the end results could not be observed.

Thus the Ki-109 failed to achieve any tangible results from its combat testing, due in major part to its inadequate performance at high altitudes. Multiple methods were employed to try and remedy the lack of performance compared to the B-29 at high altitudes during the beginning of 1945.

The production model Ki-109s were to be stripped down in weight and streamlined to improve climbing performance and airspeed. Their upper and side defensive guns were removed, leaving only the tail flexible 12.7mm cannon. Any equipment used for the bombing was taken out. All defensive steel plating was removed except for the plates in front of the ammunition storage and instrument panel, and the fire extinguishing systems were also removed, along with the fuel tanks inside the wings. Furthermore, the two existing prototypes were used for more substantial experiments.

The first prototype of Ki-109 was experimentally equipped with a ‘Toku-Ro Mk.1‘ liquid-fuel rocket engine in the former bomb bay, which was intended to provide 500 kilograms of thrust for 5 minutes. Though the rocket system added over 2 tonnes of weight when mounted, it was expected to increase the top speed by 70 – 150km/h from altitudes of 6,000 to 10,000 meters when active. Regardless, ground testing showed that the performance was inadequate, and the increase in weight in normal conditions without rocket power was too severe.

In February 1945, the second prototype of Ki-109 was equipped by Hitachi technicians with Ru-3 turbochargers onto its Ha-104 engines to improve the retention of power at high altitude. Much like the Ki-67I Kai (Ki-67I with turbo) before it, testing proved that the turbocharger was far from being suitable for practical use. Due to the incessant reliability issues common to Japanese turbochargers of the period, it was abandoned.

Diverted to Anti-Shipping, The End of the War

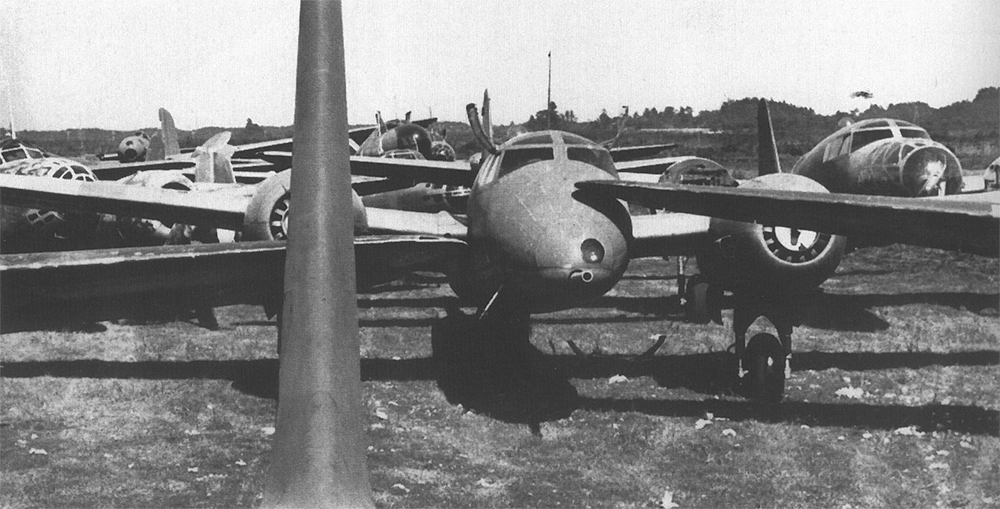

Failing to considerably enhance the performance of the Ki-109, production was halted in March 1945 during a reorganization of the priority of aviation projects. Only 20 of the planned 44 production planes were completed, due in part to the bombing of Mitsubishi Nagoya. The total count thus became 22 planes, including prototypes.

Some of the Ki-109s were serviced in the Flying 107th Sentai during the summer of 1945. The unit had been formed on November 10th, 1944 at Hamamatsu, and was trained on Type 4 Heavy Bombers in preparation for using the Ki-109 as an interceptor. However, because of the Ki-109’s inadequate performance in the role of interception, the 2nd Chūtai of the unit relocated to Daegu, in occupied Korea. Here they were used only to patrol the Korea Strait for ships and to escort the Kampu Ferry between Japan and Korea. The 107th Sentai was subsequently disbanded on July 30th to apply the personnel to more useful roles.

In July 1945, a test was carried out off the coast of Izumisano in Osaka Prefecture to appraise the Ki-109’s ability to destroy American vessels. Such a duty would have been critical in the expected decisive battle of the Japanese mainland. The first target, an Army ‘Daihatsu’ landing craft, was obliterated by a single hit. The second target was an 800-ton ship. The Ki-109 fired four shots with different attack incidences. All four shots hit, “forming a neat row on the waterline”, and the ship sank. Resultingly, the Ki-109s were to be reserved for the defense of the Japanese home islands from anticipated American landings.

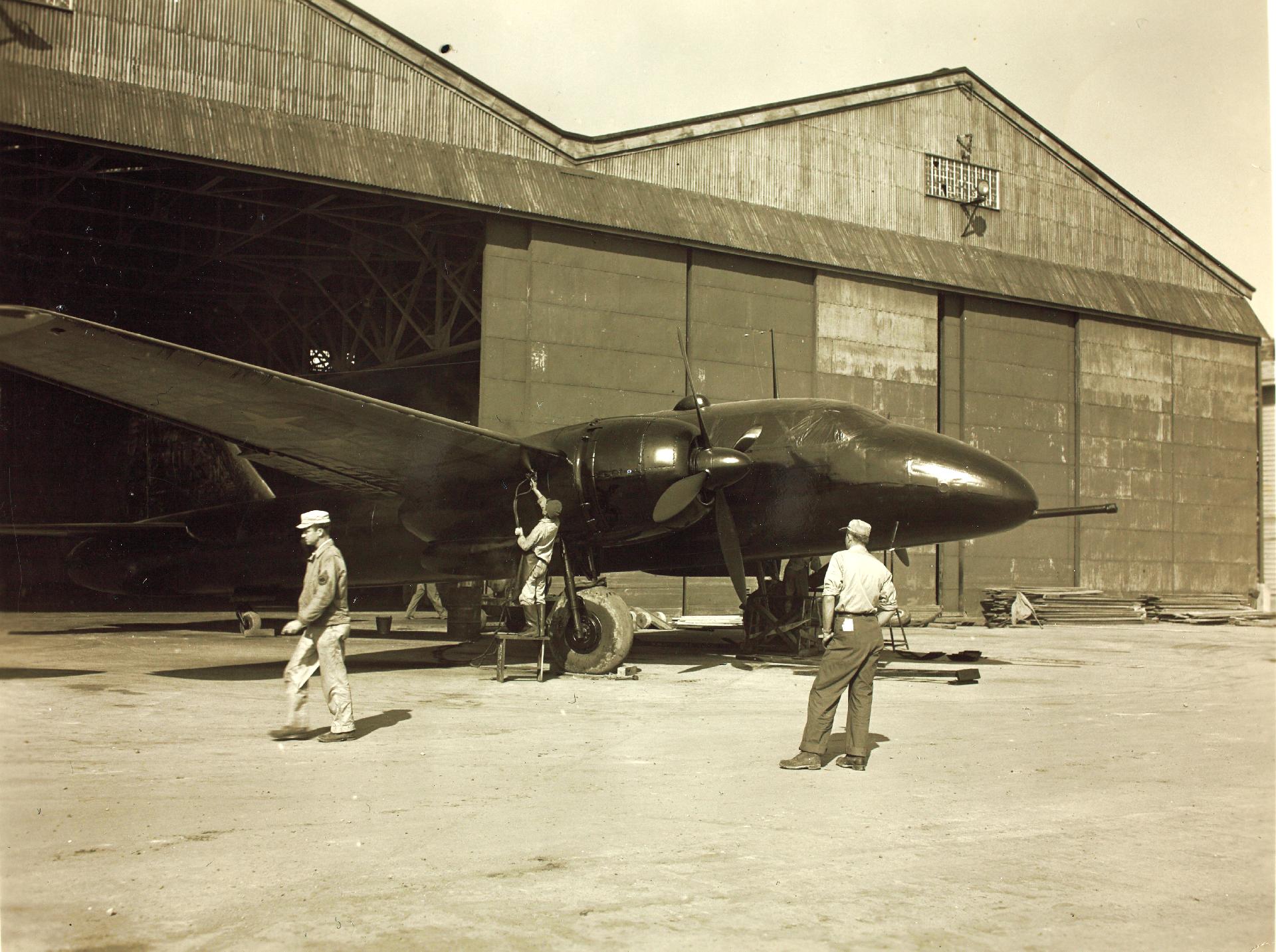

After the end of the war on August 15th, the US occupational authorities planned to requisition Ki-109 production No.’s 10 & No.11 for shipment to the USA. Photographs show that a single Ki-109 painted in overall black was loaded onto the deck of the USS Core, one of the aircraft carriers which shipped Japanese aircraft to the United States for examination. However, it is unknown if the Ki-109 was ever test flown by American pilots. Every existing Ki-109 was scrapped within a couple of years of the war’s closure, and there is no survivor today.

| Special Air Defense Fighter Ki-109 Specifications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Prototype | Ki-109 | Engine | Name | Type 4 1900 HP Engine (Ha-104) |

| Service | n/a | Output (T.O.) | 1,900 hp @ 2,450 RPM | ||

| Dimensions | Length | 17.950 m | Output (Nom.) | 1,810 hp @ 2,300 RPM (2,200 m) 1,610 hp @ 2,300 RPM (6,100 m) | |

| Span | 22.500 m | ||||

| Height | 5.800 m | Performance | Top Speed | 550 km/h @ 6,090 m | |

| Wing Area | 65.85 m2 | Climb | n/a | ||

| Weights | Empty | 7,424 kg | Range | 2,200 km | |

| Loaded | 10,800 kg | Ceiling | n/a | ||

| Wing Loading | 164 kg/m2 | Armament | Guns | Ki-109 Mtd. Cannon (7.5 cm) x 1 Type 1 12.7mm Flex. M.C. x 1 | |

| Crew | 4 (pilot, loader, gunner, radio) | ||||

This plane has the same mottled camo as prototype #1.

Conclusion

The Ki-109 was a flawed solution for a desperately necessary requirement: any means to stymie the B-29 Superfortress bombing raids that were correctly expected to severely ramp up from late 1944; an effect of the fall of the Mariana Islands.

Ultimately, the Ki-109 was useless in its original role because Japanese turbochargers could not be put into practical use in time for the war. The window for intercepting B-29s at high altitudes was brief due to this situation, which similarly choked the ability of single-engine fighters.

As B-29 raids switched to low-altitude nighttime tactics in early 1945, the purpose of the Ki-109 became redundant. Even if the Ki-109 had been fit for the role, P-51 Mustang fighters began operating as bomber escorts from Iwo in April 1945, and the fate of a bomber airframe as an interceptor was very much sealed.

Diverting this plane to the anti-shipping role was certainly a more practical mission, but under certain Allied air superiority during an invasion of the home islands, the actual efficacy is very doubtful: a Ki-109 would probably be downed before firing a single shot.

Sources

- Aircraft Machine Cannon and Ammunition Code Name Table (Ref.C14010984100)

- (1st Army Research Institute Document Binding) Primarily Related to the ‘Ki-109’ Mounted Cannon (Ref.A03032209800)

- Ho-501 Shell Diagram (Ref.C13070009100)

- Technical Data. Report No. 16A(9).

- Material on Ki-67. Jap/Ki-67/5-43.

- Data on Japanese Aircraft Shipped to the United States for Study Purposes. Report No. 15C.

- ORD TIR No.19: Research, Development and Production of Small Arms and Aircraft Armament of the Japanese Army

- Mikesh, Robert. (1993). Broken Wings of the Samurai: The Destruction of the Japanese Air Force. Naval Institute Press.

- Nohara, Shigeru. (1999). The XPlanes of Imperial Japanese Army & Navy. Green Arrow.

- Watanabe, Yoji. (2002). Unknown Sword: The Battlefield of Army Test Pilots. Bungeishunjū.

- Akimoto, Minoru. (2002). All the Formal Aircraft in Japanese Army. Kantosha.

- (2003). Famous Airplanes of the World No.98: Army Type 4 Heavy Bomber ‘Hiryū’. Bunrindo.

- Ogawa, Toshihiko. (2003). Mysterious New Planes. Kōjinsha.

- Ikari, Yoshirō. (2003). Mystery Fighters. Kōjinsha.

- Sahara, Akira. (2006). Prototype & Planned Planes of the Japanese Army 1943~1945. Ikaros Publishing.

- Sayama, Jirō. (2010). Cannons of the Japanese Army: AA Guns. Kōjinsha.

- Kariya, Masai. (2017). Japanese Army Prototype Planes Story. Ushioshōbokojinshinsha.

*August 17th 2023: Corrected information about fate of Ki-109

Hey Qaz,

There is a pic of a black painted Ki-109 (just like the one shown here) on the USS Core, with at least two other Ki-67’s and even two N1K1 Kyofu’s (and several other aircraft) all painted black. The black Ki-109 is being painted so by the fellow with the cap and spray-gun near the wing-tip, from the casual smirk I’d bet he’s almost done. Gotta love the sheen on the still-wet-paint! -Would make a great lil diorama.

Bonus- That spray-gun was originally set-up to spray from a siphon cup/jug, the cup has been removed and the paint feed hose has been jammed onto the siphon tube which is still attached to the lid of the siphon cup. Better then refillin’ a small cup a 100x, LOL! Those exact spray-guns are still widely used, EVERYDAY! (unfortunately, I can’t quite make out the brand)

Hi, ZeroTheHero,

Thank you very much for the info, I was able to find the photo of Ki-109 on the Core. For some reason, Ki-109 is not listed in the records of JP aircraft shipped to the USA of the time that I’ve seen (perhaps it was considered ‘Ki-67’). Moreover, at least one author has stated that Ki-109 was never actually shipped to the USA. But here it is evident that it was.

Possibly because photos from the USS Core are rather elusive.

I’ll correct the article soon, thanks!